First of all, there’s really no such thing as an Irish short story.

The seed was planted for my journey long ago, with a seventh grade social studies assignment to create my family tree. I already knew Grammy and Grandpa were from Chicago and New York. I hid my disappointment from my father when he said my great-grandmother was from St. Louis. I sighed; my friend’s mom was from England, and her dad had a Cherokee ancestor.

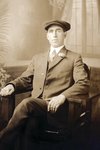

On my mom’s side, her mom was from Boston, and her dad from Los Angeles, like us. Then she smiled to remember her Irish great-grandfather, Barthly Molloy. I wrote his name on a shamrock leaf on my paper, as I filled in the other half of my family tree. One day, I decided, I’d stand where Barthly once stood, and see what he had seen.

This August, as I packed my suitcase, I included a photocopy of Barthly’s sepia tone portrait to carry with me. His tweed flat cap framed his light eyes, and a jaunty boutonnière adorned his lapel. It’s the one of the few photographs I have of him, recent acquisitions from my ancestry research, where my path converged with that of a fellow time traveler, Julie, from a different branch of the family tree. Over the past two years she’s become a pen pal and friend, as we’ve shared family photos and information, filling in the blank pages of the family history, and signing our correspondence, “Cousin.”

My destination was County Galway, the place where I landed 30 years ago, with a compass and a map in my backpack, and wondered aloud to Pat, my Irish friend I made along the way, if our ancestors had met. “I knew the moment we met you were a Galway Girl,” he’d said. The gift of the Blarney, I’d thought quietly.

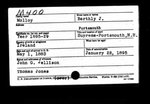

Years later, my research would lead me to a copy of Barthly’s immigration card, and the name of his hometown in County Galway, Oughterard (“Uachtar Ard” in Irish, “the height on the upper side of the river.”) I remembered Pat identifying me as a Galway Girl.

The old church was there, where my great-great-great grandparents brought Bartholomew Joseph Molloy to be baptized when he was two days old, and where he returned as a widower from America, to remarry. His home was a stone’s throw from the church. His final resting place was nearby, beyond the remaining walls of a stone chapel. I’d mapped it out, and conferred with Julie. “On the way to the church you’ll run right into the house,” she assured me, and emailed me the coordinates to the headstone in the cemetery. These events in the life of Barthly Molloy would provide me with my itinerary.

As I looked below to see the patchwork quilt of green fields, stitched together with stone fences, I remembered the first time I’d gazed upon it from a plane window. The sight filled me with the same anticipation.

My cabbie, Liam, was waiting when I arrived at Shannon Airport. “Hi, Liam!” I waved. We’d corresponded by email and I’d proposed my itinerary—with a side trip to Aughnanure Castle, and the Quiet Man bridge. As it turned out, his was the only cab company in Oughterard, population 1,319, and he was available.

On the hour and a half drive to my ancestral home, like any good cabbie, Liam described the landmarks along the way, noting the remains of a derelict castle on the side of the freeway, university buildings, and he even pointed out a rainbow.

Liam asked where I was from, and when I said I was originally from California, but recently from the smallest state, Rhode Island, he responded, “Ah, yes, the Boston Red Sox.”

Coincidences start adding up

I mentioned the only book I could find on Oughterard, was by Jess Walsh, who, by the way, had the same surname as my great-great-great grandmother. “Oh, she lives right over here,” he casually mentioned, with a nod over his left shoulder. Before I knew it, he’d pressed her number on his cell phone mounted on the dashboard. “Hello, Jess, Liam here. I have a lady looking for the Walshes…” This was the first of many coincidences I would encounter on my trip.

“Tell her I have her book!” I whispered.

On the road, the miles of picturesque rural settings gradually changed to more established towns. On the subject of Walshes, I referred to Barthly’s house in Oughterard, down the street from the church, owned by a Nora Walsh as recently as 2009. Julie had mentioned something about a funeral home, and I’d seen Walsh’s Funeral Directors on a Google street view of Oughterard.

Again, Liam reached for the call button on his phone, saying, “Dermot Walsh,” in explanation, as the phone rang. I heard a man’s voice on the line. “Hello, Dermot, Liam here. I have a lady here looking for the Molloy house…” I wondered how many Walshes lived in Oughterard. Dermot explained the Molloy house was two doors down from his business, and currently owned by Mr. O’Toole. I began to feel like a character in a BBC miniseries.

Liam smiled at me in the rearview mirror and summarized, “Oughterard is a lot like Rhode Island.”

My hotel was located in the town square, which I’d chosen for its proximity to Barthly‘s footsteps. There I met Yvonne, whom I’d communicated with by email as well. The new restaurant employee was an 18-year-old young lady by the name of Molloy. “You’ll have to meet Antoinette Lydon,” she decided, writing down the person’s contact information. “She’s a local genealogist.” Not even inside my hotel room yet, I already had three leads.

Eager for adventure, but too hungry to explore, I walked across the square to a restaurant, among the buildings festooned with tiny triangular flags in the colors of the Irish tricolor flag, which ran from one roof to another across the street. My table was beside a session band of two fiddlers and a banjo player who were playing the jig, “Calliope House.” As the three musicians were bathed in lights, and the sweet sounds of the strings filled the room, I was transported to the past on my first night back in County Galway.

The musicians took a break as a waitress replenished their pints of beer. I thanked them for the song, and the woman fiddler asked if there was anything I’d like to hear. “The Black Velvet Band,” was my request. Noting my accent, her fellow flautist said, “I’ll play you an American version.” Irish music, I’ve found, is either very happy, or very sad. So after a very happy song, followed by a very sad one, I floated back to the hotel, imagining the discoveries that awaited me in the morning.

After a breakfast of bracing Irish tea with milk and brown treacle bread, and under a light mist, I headed around the corner towards the Church of the Immaculate Conception. Julie had been right. On the way, there was the little house situated on a corner, partially below the level of the sidewalk, two doors down from Walsh’s. Its two front windows, dressed with lace curtains, were obscured by bushes. It had a large chimney adjacent to the next building, and a smaller one towards the center of its shingled roof. Dermot Walsh had remembered it with a thatched roof.

The front door, in a blue almost as bright as the house, had a latch instead of a knob. I stood there for quite some time, picturing the house its former glory, like White O’Morn Cottage in “Quiet Man.”

Of course, I eventually knocked. I wasn’t planning on it. I began to rehearse what I might say: “Hello, Mr. O’Toole, I’m Erin O’Brien…” I knocked again. “Hi, my name is Erin, and my great-great grandfather Molloy lived in your house.” Finally, I walked around to the back of the house. The yard was completely enveloped in morning glory, and enclosed by a cement wall. Maybe Barthly and Mary had a vegetable garden back there; perhaps they cooked over one hearth, and sat together beside the other in the evenings.

The mist cleared as I continued down the street towards the church. I pictured the pen and ink rendering of the original building, as it looked in 1840, to imagine the Molloy family there.

There it was ahead of me, its grey gothic tower looming among the very treetops. Arches beckoned me to pass through them. Behind the church, three tall Celtic crosses in the grass marked the graves of former pastors. I could hear the river rushing beyond the stone wall and the trees as I came nearer.

Lighting a candle

Inside, the church the walls were warm with light, a golden hue. A wedding coordinator was placing the final touches on the pews. As she silently worked, I admired the wood floor, the black and white tile aisle, and the small chandeliers which hung above the stained glass windows, one of St. Patrick. The baptismal font was made of Connemara marble with a wooden lid. I imagined Barthly’s parents and godparents, and an old monsignor, in this very spot, that morning in 1863.

A sacristan greeted me and I introduced myself, sharing the reason for my visit. Father Connolly had responded to my email, and suggested I write a 50 to 70 word family history, which he offered to publish in the parish bulletin two Sundays before my arrival. The sacristan had remembered reading it, and retrieved the most recent bulletin, which we scoured for my notice.

She saw me before the candles, and took some coins out of her pocket, placing them in my hand. “For your special intention,” she nodded. I thanked her, and we said goodbye. Alone in the church, I lit one of the candles in gratitude.

The sun was out, and in front of my hotel I noticed a woman had approached Liam’s cab. She carried a metal grocery basket on her arm and was deep in conversation with him.

It was Louise, Liam’s wife, who needed a ride home with her perishable groceries. Liam introduced us, and because it was in Ireland, Louise invited me to visit next time I was in Ireland.

Power’s Pub, trimmed in red, with its thatch roof and red door, beckoned from across the street. A chalkboard sign outside read, “If passing and you need the loos please feel welcome.” In the entrance, Cead Mile Failte (“A Hundred Thousand Welcomes”) was painted overhead. Inside, the fireplace mantle was decorated with framed holy cards, a painting of John Wayne in Quiet Man, and a Guinness mirror hung above it.

I was shown to a table by the window. When the waiter heard me speak, he asked where I was from. “Rhode Island,” I said, prepared to explain it was near Boston. Then the waiter wanted to know where in Rhode Island. “Warwick,” I answered. Of course, our waiter had worked in Boston, and had traveled to Warwick often for work for the May Company department store.

Messages from both Jess, the local photographer, and Antoinette, the genealogist, were waiting for me when I returned to the hotel to make tea with the electric kettle in my room. I was to meet them both at the courthouse at 10 o’clock the following morning. Naturally, they were acquainted.

On the road to the courthouse, the river kept me company as it gurgled by. The building turned out to be a former courthouse, now a community space. When I walked in the empty room, I looked up to see a woman waving from the top of a corner staircase. It was Antoinette. Her office was the lone room upstairs, where her computer screen displayed the Oughterard Heritage website. It dawned on me she was the website administrator who’d contacted me, when Julie answered my query about Barthly Molloy. “Yes,” she smiled, “I’ve brought a lot of people together.”

A smiling Jess appeared at the top of the stairs, her arms laden with some of her books. The three of us sat in front of the computer screen, as Antoinette asked for Barthly’s birth, death, and marriage dates, which I supplied. Each of us curious to learn where his parents lived in Oughterard, I promised Julie I’d investigate. The Molloy address didn’t appear on the baptism documents, but Antoinnette said there were some people in town she could talk to, and she’d contact me.

A peaceful resting place

Jess’s husband was a Walsh, but Jess wasn’t familiar with the Walsh who was Barthly’s mother. She asked where I was off to next, and I told her the final stop on my pilgrimage was to Kilcummin Cemetery, to visit Barthly’s grave. Since she was traveling in that direction, she offered me a ride. She presented me with her photography books, signing them for me.

A few minutes later, as Jess pulled up alongside the cemetery, another car arrived, parking in front of us. It was Antoinette, who’d decided, “I thought you might need a ride back to the hotel.” I was relieved not to be left on my own in an old graveyard to find a headstone.

There was no sign at the entrance to the cemetery, only an opening in the wall. There stood the remaining portion of the derelict chapel, just as Julie had described, the uppermost stones festooned with dried vines, while lichen crept up from the earth.

Antoinette carried her GPS device as we three traversed the undulating grass of the graveyard. Part of her work on the Oughterard Heritage site includes the Kilcummin Cemetery Mapping Project. The earliest gravesite dates to 1747.

We reached Barthly’s headstone where the old chapel served as a backdrop. I’d come to the end of my pilgrimage, and wasn’t sure if it would be an emotional moment when I stood at Barthly’s final resting place. “Hi, Barthly,” I smiled, as if to introduce myself. I’d forgotten flowers. A lonely dirt-filled terra-cotta pot was beside the grave where his second wife, Mary, rested beside him. I recalled the end of an Irish blessing: “…and may you die in Ireland.”

I had 20 euros left in my wallet. Antoinette promised to pick out a plant or flowers to leave for Barthly the next time she was at the cemetery. When I enclosed the bills in an envelope, I added a note for Barthly, struggling momentarily with what to write. Perhaps I should introduce myself, or mention my mom remembered him, or thank him for the life I’ve had because he was brave enough to immigrate to the United States. I decided on a simple message: “With affection, Your great-great granddaughter, Erin.”

I had not only walked in his footsteps, but found myself fondly attached to his hometown and its inhabitants.

The next day, on the way to the airport in Liam’s van, I looked at the lush green fields of cows, and sheep and horses, separated by stones that had been dug out of the land. As I dreamt, I was already planning my return trip.

Liam broke the silence. “Yesterday at the airport I picked up four guys from Rhode Island.”

Comments

No comments on this item Please log in to comment by clicking here